The last time I read a polemical book with the same intensity and audacity as The Message was in January 2021, when I read Between the World and Me. And guess what? Ta-Nehisi Coates authored both books! Perhaps it’s most likely that when we set out to reclaim what was once ours in the hands of others, confrontation becomes inevitable.

I borrow from the theme of this year’s Aké Festival – Reclaiming the Truth – to title this review because it’s a counter-narrative against the dominant Western political discourses on slavery, black identity, and Palestine. Blending travelogue and memoir, The Message traces Coates’s visits to Dakar, Senegal; Chapin, South Carolina; and the West Bank and East Jerusalem in Palestine. The latter trip, as we see in the book, leaves a deep impression on Coates.

How I discovered this publisher’s son, whose mother once punished by asking him to write essays, is something I love telling with a renewed relish. In a movie (later identified as The Equalizer 2), a friend watched Denzel Washington recommend Between the World and Me to an adolescent boy. Trusting Denzel’s taste, he called and asked me to look out for the book. I did. That was in 2020, and even back then, as a national correspondent for The Atlantic, refusing the offer to write for flashier American media outlets, Coates had established himself as one of the finest public intellectuals in the United States.

While Between the World and Me takes the form of a letter to his then-adolescent son, Samori, wherein Coates expresses his legitimate concerns for his son about the consequences of living in a black body in the United States, this masterpiece, The Message, is addressed to his writing students at Howard University, whom he refers to as comrades. He asks them to ditch the idea of writing for writing’s sake, and reminds them that their school was founded in the first place to combat the shadow of slavery, something Coates believes has not yet retreated. “This meant that we could never practice writing solely for the craft itself,” he writes, “but must necessarily believe our practice to be in service of that larger emancipatory mandate.”

Coates says his journey to becoming a writer began with his love for language and recounts some poems that possessed and haunted him right from childhood. He advises his students not just to write, but to write something that would haunt their readers. “Haunt. You’ve heard me say this word a lot.” He says, “It is never enough for the reader of your words to be convinced. The goal is to haunt—to have them think about your words before bed, see them manifest in their dreams, tell their partner about them the next morning, to have them grab random people on the street, shake them and say, ‘Have you read this yet?’”

In this message to his students, Coates is not asking them to craft their words only in dulcet poetry and lyrical rhythm; the title of the opening part of the book, Journalism is Not a Luxury, says it all regarding what he required of them. He wants them to be bold and courageous, to speak on unsettling political matters, and to tell the truth that hardly anyone tells. He says, “…I lived in a house overflowing with language organized into books, most of them concerned with ‘the community,’ as my mother would put it. And so it was made clear to me that words could haunt not only in form, not only in their rhythm and roundness, but in their content.”

Before we enter into the account of Coates’s travels, he tells us that it has been almost two years since the last time he met his students, who were eager to scrutinise his essay after promising to submit one to them for the purpose. “You were giddy, in no small part, to turn my own lessons against me—to point out where I was vague, verbose, or just lazy.” He wrote. “But when the semester ended, I had produced no essay.” But he had a reason, “I’ve been traveling—Senegal, South Carolina, Palestine.” In the end, Coates presented this book to his students in lieu of the promised essay. “But I’m home now, and with me I bring my belated assignment—notes on language and politics, on the forest, on writing.”

Coates stands among contemporary writers who inherit the tradition of French masters like Flaubert and Barthes, sharing their obsession with crafting lessons on the art of writing within their works.

His trip to Dakar was a homecoming. Having traced his African ancestry to Senegal, in a prelude to what inspired his homecoming journey, Coates wrote:

“I think if he tried to describe the forces shaping his life, my father would see his own actions first: his credits, his mistakes. But if he widened the aperture to the world around him, he would see that some people’s credits earned them more, and their mistakes cost them less. And those people who took more and paid less lived in a world of iniquitous wealth, while his own people lived in a world of terrifying want. And what my father would have also seen is that he was confronted not just by the yawning chasm between wealth and want, but by the stories that sought to inscribe that chasm as natural. He would have pointed to the arsenal of histories, essays, novels, ethnographies, teleplays, treatments, and monographs, which were not white supremacy itself but its syllabus, its corpus, its canon.”

Coates said the weight of his first trip to Africa was directly tied to that canon and to the work of men like Josiah Nott, a nineteenth-century anthropologist, epidemiologist, and student of civilisation. Coates argued that Nott had profited twice from slavery: as a slaveholder and by his chosen field of study. His opinion on Nott in this book, to put it mildly, is scathing:

“Nott wrote to his mentor, the anthropologist Samuel Morton, in 1847.

‘I am the big gun of the profession here.’ That profession had but one aim —assembling all the knowledge Nott could summon to prove we were inferior and thus fit for enslavement.”

At this point, Coates reflected on how oppressors used stories to justify their atrocities. “It may seem strange that people who have already attained a position of power through violence invest so much time in justifying their plunder with words.” He wrote. “But even plunderers are human beings whose violent ambitions must contend with the guilt that gnaws at them when they meet the eyes of their victims. And so a story must be told, one that raises a wall between themselves and those they seek to throttle and rob.”

Coates observed that this trait of using words to justify plunder is not only common in men, but also in children. He took us to his childhood:

“When I was a boy, back in Baltimore, it was never enough for some kid who wanted to steal your football, your Diamondback dirt bike, or your Sixers Starter jacket to just do it. A justification was needed: ‘Shorty, lemme see that football,’ ‘Somebody stole my lil cousin bike just like that one,’ ‘Ay yo, that look like my Starter.’ Debating the expansive use of the verb “see,” investigating the veracity of an alleged younger cousin, or producing a receipt misses the point. The point, even at such a young age, was the suppression of the network of neurons that houses the soft, humane parts of us.”

“For men like Nott,” he said, “who sought not to plunder toys or kicks but whole nations, the need was manifestly greater.” And his reflections on the work of Nott brought us back to the call he had earlier made to his students that their writing must haunt the readers. Thus, haunted by the despicable description of Africans as sub-humans by men like Nott, and the systematic racism against blacks in the United States, a trip to see this Africa for himself became necessary.

He visited the Atlantic Ocean and found himself immersed in thoughts regarding the men, women, and children shipped to the Americas on the back of the mighty water. “I went to Senegal in silence and solitude,” he wrote, “like a man visiting the grave of an uncertain ancestor.” These emotions would culminate in tears on his way back from Gorée, the famous island memorialised in David Diop’s Beyond the Door of No Return, a place where enslaved Africans were severed permanently from their ancestral lands. “On the way back from Gorée,” he said, “as the shuttle broke through the waves, for the first time, I was stunned to find tears welling in my eyes. I felt ridiculous.”

On his last night in Dakar, Coates recounted a rendezvous with some Senegalese writers, whom he described as “people who also knew the fire.” He said, “I knew slavery and Jim Crow, and they knew conquest and colonialism. And we were joined by an inescapable act: The first word written on the warrant of plunder is Africa. Someday there will be more—and I guess there already is: in Afrobeats and Amapiano. And I guess there always was: in jazz and our rituals of dap. And the lines are bending in amazing ways.”

By his account, Coates didn’t leave Senegal a sad man despite reporting earlier about a sadness in him that expanded “from a pinhole until it was wide as the sea itself.” Halfway through the meeting with fellow writers, a young woman “with a look of amazement on her face” joined the party and spoke to Coates that she was a grad student working on a dissertation about his books. “Now the amazement was my own: There I was on the other side, among family divided from each other by centuries.” He concluded, “I had come back. But my own writing had gotten here first.”

Haunt. I believe you remember this word from where Coates tasks his students with writing contents that haunt. Around the same time George Floyd was killed, Nikole Hannah-Jones won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for her introductory essay in The 1619 Project, which argued for America’s origins not in the Declaration of Independence but in enslavement. “Nikole is my homegirl,” said Coates, “and like me, she believes that journalism, history, and literature have a place in our fight to make a better world.”

There was a backlash. President Trump initiated “The 1776” project as a response to counter the idea that America was not built on racism and slavery. Some of his supporters explicitly linked the 2020 riots on the street to the writing by calling it “1619 riots”, and the White House issued Executive Order 13950, targeting any education or training that included the notion that America was “fundamentally racist,” the idea that any race bore “responsibility for actions committed in the past,” or any other “divisive concept” that should provoke “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.” This order was revoked after Trump lost the 2020 elections, but state-level variants had already spawned, with Hannah-Jones scotched from her tenure offer at North Carolina State University.

Coates points out the obvious. Here are people who loudly exalt the values of free speech but are aggressively prosecuting orders that suppress blacks from telling their stories. “But the simple fact is that these people were liars,” he writes, “and to take them seriously, to press a case of hypocrisy or misreading, is to be distracted again.”

Despite the war over scholarship and art, demands for black literature increased in the United States. “But in the months after George Floyd’s murder, books by Black authors on race and racism shot to the top of bestseller and most-borrowed lists. Black bookstores saw their sales skyrocket. The cause for this spike was, in the main, people who had been exposed to George Floyd’s murder coming to suspect that they had not been taught the entire truth about justice, history, policing, racism, and any number of other related subjects.”

This brings us to his second trip, recounted in the book. The trip is directly related to the haunting effects of Between the World and Me on both his admirers and traducers. He travels to Chapin, South Carolina, to meet a school teacher by the name of Mary Wood, who insists on teaching Between the World and Me despite calls on her to drop the book. Campaigns were made on Facebook for and against the book. A board meeting was held to decide the fate of the book in Mary Wood’s lesson plan. The book won.

“Literature is anguish,” Coates argues, but its ultimate gift is enlightenment. He contends that the attacks against Black scholarship and art on racism and slavery were never about protecting children who, in their words, “feel uncomfortable” or “ashamed to be Caucasian,” but to prohibit enlightenment.

The book culminates in Coates’s 2024 trip to Palestine for a literary festival. He discovers that the state owns the rainwater and Palestinians need a permit, which is mostly not given, to collect it. Last year, shortly after its publication, I encountered a scathing New Yorker review that took particular issue with this section. The reviewer didn’t scold the book for its contents but for what it failed to mention. It was something like “We have heard the victims’ narrative, why ignore their oppressors’ perspective?” I find it funny, to say the least. But Coates has already told us “even plunderers are human beings whose violent ambitions must contend with the guilt that gnaws at them when they meet the eyes of their victims.”

This part of the book started with a quote by Noura Erakat: “We have all been lied to about too much.”

Upon arrival, Coates visited Yad Vashem, the memorial site to the six million victims of the holocaust, where he spent time and mourned. But after some days in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, he would describe the memorial site as “a grand narrative of conquered ancestors built by their conquering progeny.” He wrote, “I can see that, now that I have walked the land. But there was a time when I took my survey from afar, and invoked this same land to service my own, more narrow story.” He expressed his regret over peddling Israeli propaganda in the past to his students. “It hurts to tell you this. It hurts to know that in my own writing I have done to people that which, in this writing, I have inveighed against—that I have reduced people, diminished people, erased people. I want to tell you I was wrong.”

Coates reported what he saw in Palestine: a slow but constant ethnic cleansing by a vicious apartheid regime. “Everywhere I went that week, in the Occupied Territories, in East Jerusalem, in Haifa, and in the stories told by Palestinians and even by Israelis, I felt that the state had one message to the Palestinians within its borders. The message was: “You’d really be better off somewhere else.” His verdict on the state of Israel is brutally honest. “I don’t think I ever, in my life, felt the glare of racism burn stranger and more intense than in Israel.”

He said a lot about his visit to Palestine, but perhaps none of his observations struck me as much as this:

“I’m not sure when, exactly, during my visit, I first heard the term the Nakba…The phrase, which means ‘the catastrophe,’ originates in the driving of some seven hundred thousand Palestinians from their homes in 1948 and continues in the perpetual process of ethnic cleansing I saw in my ten days. By the end of my visit, I understood the Nakba as a particular thing, ranging even beyond any analogies with Jim Crow, colonialism, or apartheid. It is not just the cops shooting your son, though there is that too. It is not just a racist carceral project, though that is here too. And it is not just an inequality before the law, though that was everywhere I looked. It is the thing that each of those devices served—a plunder of your home, a plunder both near and perpetual.”

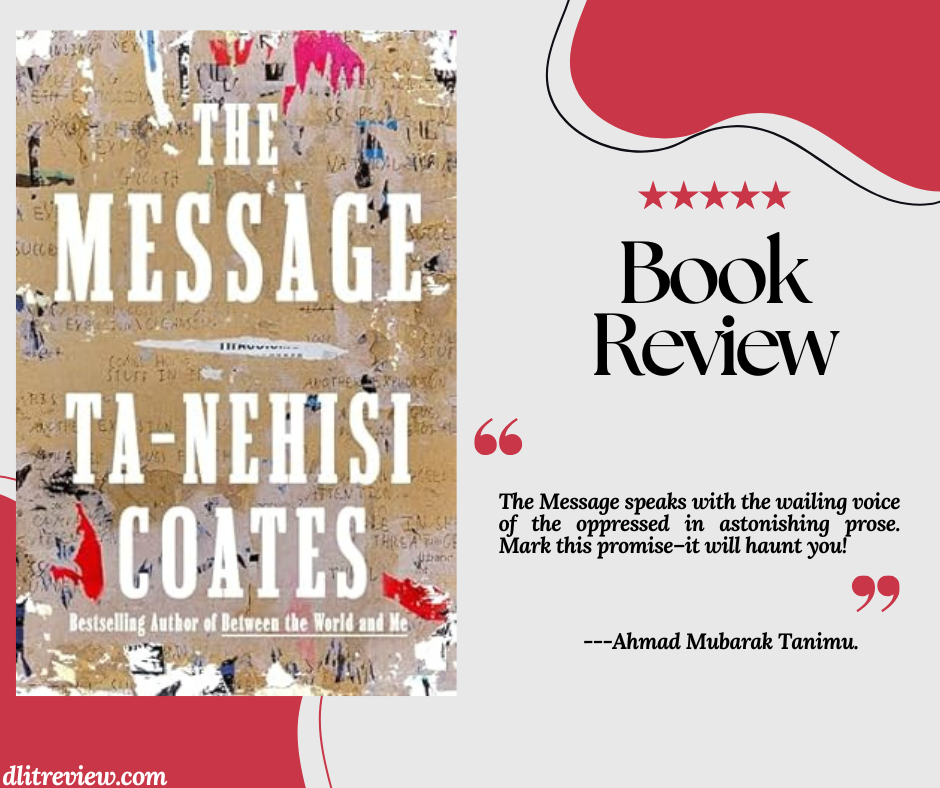

Having laid bare the case that the Israeli occupation of Palestine is a moral crime, one that has been all but condoned by the West, The Message speaks with the wailing voice of the oppressed in astonishing prose. Mark this promise–it will haunt you!

Alex

Young Dabold