This is a socially conscious poetry collection through personal narratives and reflections on war and other tragedies. Poetry comes from emotion. Love is the most ecstatic of emotions, and this poet appears to be saying, “If this is an emotional craft, then why can’t I begin from its awesome side?” The last two lines of the first poem in this collection seem to acknowledge the limits of words in expressing our emotions:

“Where do words go

When a poet falls in love?”

Well, this is a question that has already been answered by the Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, who says, “What we feel is beyond words. We should be ashamed of our poems.”

In the second part of the collection, the poet switches from romance and appears to readers in the toga of a concerned global citizen. She reflects on the Naqba in Gaza. Those commentaries we read on the website of Aljazeera from Marwan Bishara and others are presented to us here in the form of sorrowful songs.

The first poem in this part of the book, “This is How We Teach the English Alphabet”, starts with “A: for airstrikes, arriving to airlift people to an early grave” and ends with “Z: for zero, the number of times we tasted peace”. The poem is one of the outstanding pieces in the collection owing to its creative and evocative strength. It’s a loud testament to the credibility of the poetry of this poet.

I’m not much of a poetry reader because barring anthologies, the only four poetry collections I ever read in my life are in the last two months and this collection is the first. I find the fourth poem in this part of the book reminiscent of JP Clarke’s “The Casualties”. Whilst Clarke’s poem seeks to unravel the victims of the Nigerian civil war beyond the ones we see on the open surface by saying “The casualties are not only those who are dead; they’re well out of it”, Nasiba’s “The Price of Homelands” interrogates with a similar tone, albeit rhetorically, the actual cost incurred by Palestinians in losing their homelands.

“The price of homelands is not in dollars or pounds,

It is in the bodies of children who become adults,

When a blast blows away their childhood”

And as Clarke’s poem mentions the actual casualties from his point of view, so is this one in the subsequent lines which give us the list of the ‘price-payers’ when a homeland is lost.

In the third part of the book, the poet returns from her sad trip from Palestine to her own backyard in Northern Nigeria and we see her mourning the shards of our broken country. The first poem here, “I Can’t be Present”, appears to be giving valid reasons to those seeking to relocate from this bedridden country plagued by the ailment of misery.

The first verse of the poem reads:

“I can’t be present here,

Where home is a synonym for chaos,

Where gunshots are the lullabies that lull

Children to a sleep they never wake up from.”

The first line from the first verse is a refrain the poet uses to begin all the five verses of the poem and still closes the poem with it. The eighth poem in this part of the collection is also another song for japa. In the ninth poem, the poet contemplates on how we unite or divide depending on the convenience of the situation in this country:

“We are one nation,

When united in victory.

We are two regions,

When visited by calamity.”

The poem reminds me of one of my happiest days as a Nigerian. That Friday evening in the summer of 2018 when Ahmed Musa scored a brace in a world cup game against Iceland in Russia. This poet is right. We are one, when we win. It’s a setback that pushes us to maliciously allocate blames.

The next poem after this in the collection is something strikingly similar to Dike Chukwumerije’s “The Wall and the Bridge”. The poet titles it “An Anthology of Stereotypes” and cries out on how ethnic identity trumps over all our qualities as humans in this country. This part of the collection is an invaluable contribution to the conversation on our national malaise.

If there is any central theme that interconnects literatures of black origin, then it is the question of identity. This poet stands strong against the sweeping tides of stereotypes and subtle condescension to present herself as a black and a Hausa woman. A proud one for that, in this fourth part of the book. The poems here are directly personal and can be tagged “a self-introduction”. This is the part that houses my favourite poem in the collection, “Poet of Light”.

While reading the collection, I suffered from the images of pain, grief and loss in the poems preceding this one. So, reading this line in the poem was accompanied with a cherished awe, “there are tonnes and tonnes of melanin in my skin, but I am light”. It came to me with visualised lively images of Maya Angelou performing the poem to thousands of audiences. I jumped off my seat and exclaimed “God! This is Maya-esque!”

In the fifth part of the collection, this poet comes to us this time as someone who is conscious of her surroundings. She observes and reflects upon even what seems like the most negligible of happenings. The part is titled “Pickled Moments”, a pointer to where the collection derives its title from. I don’t know whether it is a coincidence or a meticulous arrangement, the first poem here, “Art for the Mundane”, summarises the whole body of the collection.

The book begins with love and ends with loss. The final part is a buffet of loss that serves readers with eighteen poems discussing the dynamics of loss. The first poem here, “Everyday Someone Dies”, at the centre of it is a reflection on the human weakness regarding their consistency with sin even after a resolution to abstain. This is similar to Ismail Bala’s “Emotion: Addiction” from his collection, “Ivory Night”.

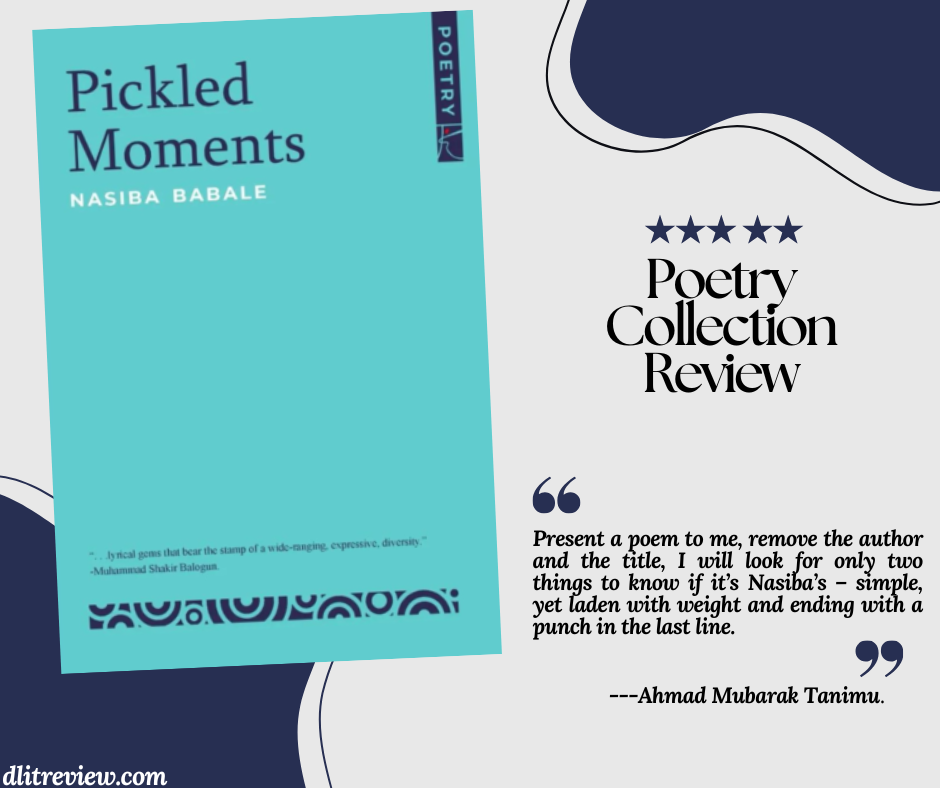

I haven’t read enough of Nigerian poetry collections to have the wherewithal for audacious assertions about this poet, but I’m pleased with her art which makes poetry to be intractably easy without compromising its prestigious elegance and the uniform identity that her poems wear. Present a poem to me, remove the author and the title, I will look for only two things to know if it’s Nasiba’s – simple, yet laden with weight and ending with a punch in the last line.