The first time I stumbled across Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, it was through my sister. She was preparing for the UTME, and the book was one of either WAEC or JAMB’s recommended texts. I still remember spotting it on her desk and wondering, “Purple hibiscus? What kind of flower is that?” Growing up, the only hibiscuses I saw in front of people’s yards were red, so the book was already a promise of something rare. I was hooked even before I opened it.

In summary, Purple Hibiscus tells the story of the Achikes, a family living under the high-handedness of their father, Eugene. Everything they do, they do to please him, to stay on his good side. He’s a devout Catholic and a successful businessman, but he’s also a man who rules his household with an iron fist. His religious fanaticism demands that his family be as pious as he is. His inability to attend top-tier schools as a child means Kambili and her brother, Jaja, must have stellar results; anything less invites severe punishment. Any form of disobedience, even the smallest, attracts his wrath. Not even their mother, Beatrice, is spared.

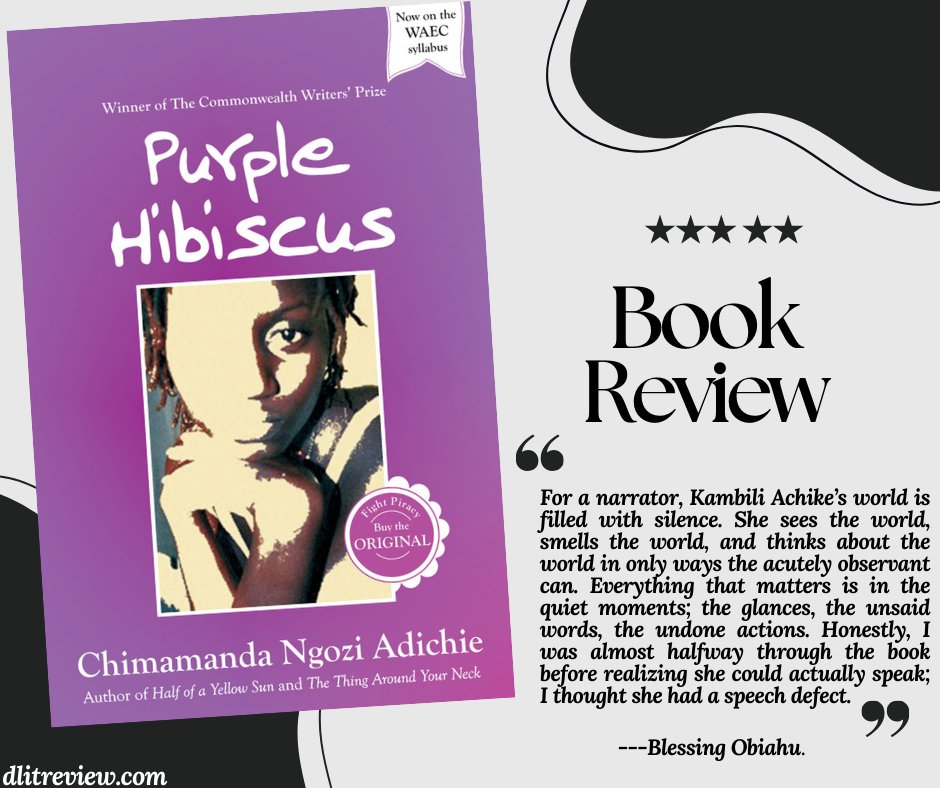

For a narrator, Kambili Achike’s world is filled with silence. She sees the world, smells the world, and thinks about the world in only ways the acutely observant can. Everything that matters is in the quiet moments; the glances, the unsaid words, the undone actions. Honestly, I was almost halfway through the book before realizing she could actually speak; I thought she had a speech defect.

But the book opens with a shattering of that silence, and so begins a look into the years of silence, and how that moment was only an outward manifestation of the buildup to that shattering. I love the first line and its tributary to Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

Purple Hibiscus’ First Line

What truly stands out about this book, even after multiple readings, is its quiet power. I love the (almost) perfection of Purple Hibiscus. Adichie doesn’t bombard you with loud descriptions, but her narrative is so vivid that you can almost feel the weight of Papa’s overbearing presence, hear the slap-slap of Mama’s flip-flops, or smell the spices clinging to Sisi. Through Kambili’s eyes, we see a household that looks perfect on the outside but is slowly crumbling within. And then there’s Aunty Ifeoma and her children, a stark contrast to her brother Eugene’s household, a breath of fresh air, and her experimental purple hibiscus in Nsukka. Purple Hibiscus is rich with details, and so is the symbolism. It took a re-read for me to understand what the flower means. Freedom, defiance; everything Kambili and Jaja yearn for in their rigidly controlled lives.

At the time, I was transitioning out of my Harlequin romance phase; you know, the era of daydreams about star-crossed lovers and impossibly perfect relationships. So naturally, I zeroed in on Father Amadi and Kambili’s interactions, convincing myself something might happen between them. Spoiler alert: it didn’t. But that didn’t stop me from reading every line with wishful thinking, hoping for a spark. Now, looking back, I think I realize their dynamic was never meant to be romantic; what’s more important is the awakening, the possibilities beyond what Kambili thought she deserved. And when she finally transforms into someone who starts to see, and more importantly, believe in, a world beyond her father’s iron grip, I felt satisfied with her complete arc.

Fast-forward to now, and I’ve read Purple Hibiscus almost four times. The fourth read came right after I heard the news of a new release from Chimamanda in March this year. That sent me back into her entire body of work. I’m revisiting old favourites, like Half of a Yellow Sun and Americanah, while catching up on those I somehow missed. But no matter how many times I pick up Purple Hibiscus, it hits differently each time. Maybe it’s because I’m older now, more attuned to the layers within the story, or maybe it’s just the magic of Adichie’s writing.

Back when I first read it, I saw Purple Hibiscus as a coming-of-age story. Now, I also see it as an exploration of power, religious extremity, and the delicate balance between love and control. I also love the way Adichie captures the theme of the duality of the human experience in this story; the beauty and the pain, the love and the violence. Eugene Achike is a complex figure; a man celebrated for his generosity and integrity in public, yet feared within the walls of his own home.

I appreciate Purple Hibiscus as one of the first novels I encountered that felt deeply, unapologetically Nigerian. I love that Adichie doesn’t try to dilute her cultural references. I love the experiences in Nsukka. The rhythm of Igbo expressions. Even the Catholic rituals looming large over the Achike household. This is one story that feels so real, so rooted.

Purple Hibiscus has become my favourite microcosm for fragile, yet unyielding hope.