I’ve read When We Were Fireflies, a book of 409 pages, three times, and it’s not yet three years old. “No book is worth reading once,” said García Márquez, “if it is not worth reading many times.” As a protégé of Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, I can tell with certainty that no writer, dead or living, enjoys his admiration like García Márquez. Though Ibrahim’s favourite in the García Márquez oeuvre is Love in the Time of Cholera, his own novel, When We Were Fireflies, follows the deeply magical tradition of One Hundred Years of Solitude. It solidifies him as a proper son of the soil in the literary nation of García Márquez. However, the enduring love in the book between Indo and Babayo suggests a more direct influence from the former.

Ibrahim writes with a sustained intensity of language that perhaps makes him the Nigerian leading torchbearer of the maxim from Susan Sontag, “literature is first of all, last of all, language.” However, for Ibrahim, language seems to be the beginning and the end, a quality story. He tells engrossing tales. There’s something inviting about his stories; readers rarely escape resonating with the plights and triumphs of his characters. The flair in Ibrahim’s writings compares directly to Barcelona’s domineering tiki-taka. Such a master storyteller.

Unlike the South, reincarnation is not a popular conversation in the spirituality of major cultures in Northern Nigeria. As children, my peers in the North would agree that the closest thing to reincarnation that they’ve heard in stories was of people returning to the physical realms after their death as ghosts, not as humans with a fresh life. That’s why I feel the proper artistic case for reincarnation made in this book comes from a writer from an unlikely quarters of Nigeria, the North.

Ibrahim’s status as a luminous star in the literary heavens is never a story of providence, but of diligence. Here is a writer who took his time to give a title to each of the 67 chapters of this book, where numbers could suffice. I find it thrilling, just as Machado de Assis thrilled me by doing so for each of the 160 chapters in his timeless classic, The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas.

When We Were Fireflies is a reflection on the past and contemporary history of violence in Nigeria, particularly the north, narrated through the vehicle of memory, love, art, reincarnation, family drama, and the quest for retribution.

Umar Abubakar Sidi calls this book a literary bomb. Such a befitting title, for it’s almost impossible to find the reader’s mind that this book will not blow up. The artistic and creative competence, deployed in the making of the novel, is top-notch and undeniable. The story is strange, yet convincingly believable. I think even Ibrahim surprises himself with this masterpiece.

Ben Okri’s The Famished Road has been a loner for three decades in its league of Nigerian fiction written with an outstanding level of creativity; now it has a companion in When We Were Fireflies. This novel looks at everything carefully from both a mystical and physical point of view.

The opening passage of the book reminds us of the disgraceful absence of a rail transport system in Nigeria for decades after it was built by the colonial administration, another evidence of decline and decadence since independence. Its partial restoration in the country opens the plot of this story as it takes Yarima Lalo into the landscapes of his previous lives. While reincarnation is a common trope in African mythology, Ibrahim treats it not with superstition but with logic. He uses tangible evidence to build a convincing case for his protagonist’s two past lives, achieving a triumph in absurdity.

Yarima Lalo first met Aziza at the Idu train station, Abuja. Their relationship grows gradually, and she would end up playing a significant role in the search for his lost time from his previous lives. Aziza’s character in this novel is the vehicle used by the author to demystify the mystery in the protagonist’s life. Her character, though dealing with her own family drama, asks almost every question that an inquisitive mind would regarding the strangeness of Yarima Lalo.

Haunted each night by dreams of past lives, Lalo jolts awake at the same mysterious hour: 2:14 AM. Lalo thinks he’s losing his mind, but after seeing a moving train, he becomes convinced that he indeed had two previous lives. He remembers the second life in Kafanchan in detail, but of his first life, he only recalls his murder on a train. As a brooding artist, Lalo keeps committing these memories to a canvas. But he wouldn’t discuss it with anyone. Why should he, and who wouldn’t declare him mad?

At the Idu train station, during their first encounter, Aziza asked him what time it was, and it was mysteriously 2:14 PM. Rain would push her to unknowingly seek shelter in his studio, and after realising they had met before, their relationship would grow from there. She would question some of his paintings that preserved the memories of his previous lives that kept pouring from his dreams, and gradually, he would open up to her, and with time and evidence, she would not only believe him but join him in the search for the remains of his previous lives.

There is something philosophically similar and striking between the character of Yarima Lalo and Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart. Both appear to be terrified about the prospect of being seen as weak, and thus motivated by fear to achieve great things. Where they differ is that the character of Lalo is not as stern and stubborn as that of Okonkwo.

Lalo believes each time he returns to this world, something is taken from him, and this time, he suspects his manhood to be taken. Fear initially restricts him from seeking medical help, and instead, he builds muscles and joins the army in order to be seen as a man. Kande, his mother, sees this as a psychological hangover of the mockery he received from boys as a kid. When she asks him on one of those days she’s awake from her long sleeps that springs to days and weeks, about his relationship status, he says “love is overrated”. Her response stuns him, “How about fear,” she asks, “is that overrated too?”

The character of Lalo stuns not only Aziza, Indo (his love in the first life), and Turai (his love in the second life) – the only people who are aware that he lived many lives in the story – but also the spirits’ children, who are not actually children. They are shocked that he sees them, and those who recognise him amongst the spirits are stunned by the fact that he escapes back to the physical realm.

Lalo now lives with the freedom and certainty of an imminent third death, and he is to die for love and a woman, as his first two lives were taken by his jealous rivals. But he has to travel to Jos, Kafanchan, and Maiduguri to accomplish some missions in the quest for both revenge and redemption.

The Allusion to Dokin Iska Ɗan Filinge was perhaps the most exciting part of the novel for me, and of course, the peaceful and cheerful Jos of racecourse. There is also the vivid description of Abuja and Kano; it was this book that first influenced my decision to visit Gidan Makama. Ibrahim tells a sad story with a restrained tone that doesn’t stir up emotions in When We Were Fireflies, ranging from wars, domestic and gender-based violence, child neglect, homicide, Boko Haram insurgency, herdsmen violence, and the massacre of Shiites in Nigeria. This book really opens up the relevance of zaman makoki, how consoled mourners can be when they’re in the midst of sympathisers, because Lalo didn’t feel the pain of losing his mother until after finding himself alone.

I find Turai’s story in this novel especially interesting for its critique of the “great expectations” placed on beautiful girls, who are treated as a financial strategy to lift their families out of poverty. The story reveals the inherent fragility of this plan as she ends up with an unwanted pregnancy. Also, there is this critical conversation on marrying divorced women and not taking in their children. The refusal of Aziza’s stepfather to take her in exposes her to the vulnerability of molestation at the hands of her uncle and cousin at her grandmother’s home.

This novel is deeply philosophical and serves as a great reminder of our nothingness in the hands of time. When Lalo finally meets the people from his previous lives, he couldn’t harm any of them; time has already reduced them to something of a pity, something of a waste. Also, the novel interrogates our priorities in life and the things we are willing to lay our lives for; it simply asks the question of “Is that thing you want to die for really worth it?” For with or without us, life goes on.

When We Were Fireflies is the great Nigerian novel, says Carl Terver, and Ibrahim has written it. With all due respect, the decision of the 2025 NLNG Nigeria prize for literature to ignore the book in their shortlist might not be grounded in literary merit. May, Obioma, and Oyeku are fantastic writers, but a thousand of the shortlisted books cannot compare to this masterpiece from Ibrahim, if our loyalty lies with literary excellence.

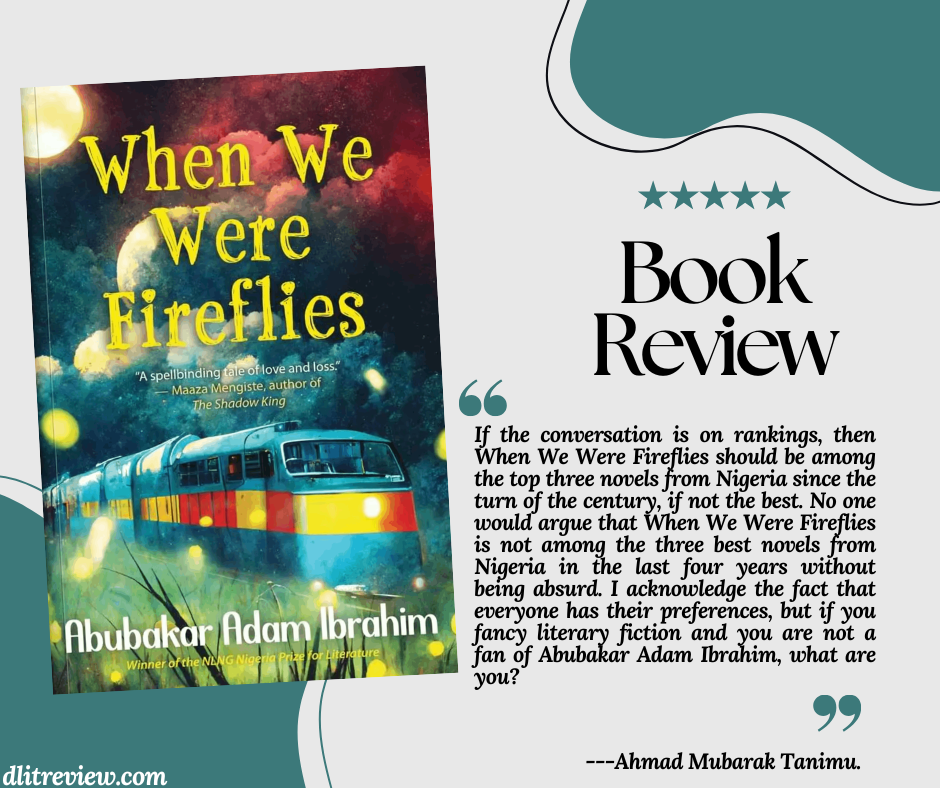

If the conversation is on rankings, then When We Were Fireflies should be among the top three novels from Nigeria since the turn of the century, if not the best. No one would argue that When We Were Fireflies is not among the three best novels from Nigeria in the last four years without being absurd. I acknowledge the fact that everyone has their preferences, but if you fancy literary fiction and you are not a fan of Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, what are you?

I’ve symbolically borrowed this review’s title: Remembrance of Things Past (also translated as In Search of Lost Time), from Marcel Proust’s seven-volume masterpiece. Widely regarded as France’s greatest novelist, Proust’s work is a fitting touchstone, as this book shares his profound themes of memory and loss. Furthermore, When We Were Fireflies reflects classic traits of French literature, including a philosophical inclination and a preoccupation with beauty. It is perhaps no coincidence that the manuscript was first drafted in France. For the writer, this novel embodies ambition, execution, and quality. For the reader? Delight!