Lola Akinmade Akerström’s In Every Mirror She’s Black is written in exquisite language. The novel explores the lives of three black women in Stockholm, each representing different social strata from the elite, middle and low-income class. Still, no class attainment in the city seems enough to shield any of them from open or subtle racism and low expectations.

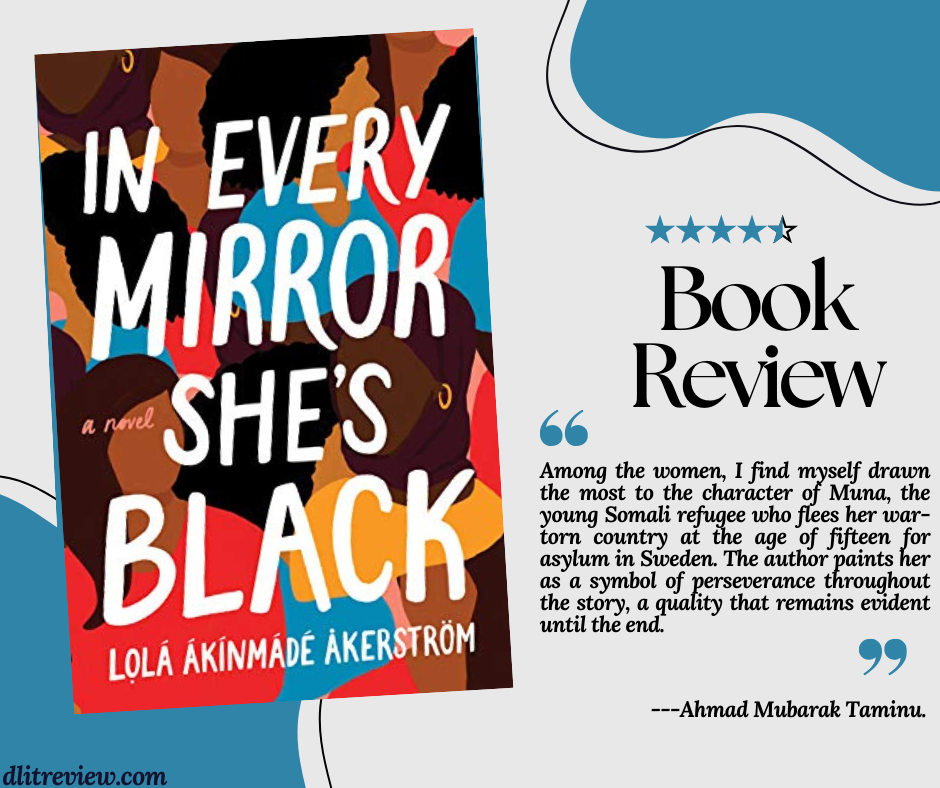

Among the women, I find myself drawn the most to the character of Muna, the young Somali refugee who flees her war-torn country at the age of fifteen for asylum in Sweden. The author paints her as a symbol of perseverance throughout the story, a quality that remains evident until the end.

Like power, love is portrayed to be transient in the life of Muna, and she keeps enduring her losses. But when trouble insists on piling and retaining her miseries, she chooses to knock on the door of death. It opens, and she reunites with her loved ones. The harsh treatment of Muna in this novel is similar to the treatment of Mariam in Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns. Pain all through with just little spells of good things.

Muna sees a lot. From seeing her bedridden father killed by the falling walls of their house during an attack on her hometown in Somalia, to losing her other family members on their way to Sweden. Her separation from her mother and brother carries an even more disturbing image. The author writes:

“Her mother, Caaliyah, and younger brother, Aaden, were buried somewhere deep at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea. Aaden had toppled off the rubber dinghy first, and she’d seen her mother reach for him before going overboard herself, her blue jilbab floating like a jellyfish until it had slipped from view. The strong arms of a man from Algeria wrapped tightly around Muna’s waist had stopped her from resembling a jellyfish too. That day, Muna learned just how loud she could scream.”

The pain of Muna increases when her lover Ahmed burns himself to death after three years of waiting in a refugee camp for residency in Sweden who refuses to come. Ahmed is from Kurdistan and the war in Syria consumed his village and his entire family. She later makes two friends; Yasmin and Khadija, both from Somalia like her. The former leaves them after a fight with the latter and the latter ends in detention after involving in a riot. Their matron, Gunhild, a Swedish woman who notices Muna’s loneliness becomes like her mother. But the woman is already dying from cancer and just days after moving in with her, the woman dies. Muna joins her the same day.

The circumstances leading directly to Muna’s suicide on the day of her death deepen my animosity for two things; alcohol and seeing a woman outside late at night. I am always concerned about a woman’s safety, whenever I see one late at night, alone and outside her home. Muna is on a night shift in her cleaning job when two drunk Swedish young men molest her on the way back home. She pushes one of them into falling on his head and dying. As she flees the scene, she decides to end it all by jumping into a moving train. A regular occurrence in Stockholm as we read in the story.

The second woman, Kemi, a Nigerian American, battles with tokenism and the drought of relationships with men befitting her status as an accomplished career woman. When Von Ludin Marketing decides to scout her from Sweden to the United States it’s solely to have a person of colour on their board of directors despite her impeccable pedigree.

Brittany, a perfectly beautiful black American woman of Jamaican descent, marries Jonny, the heir to the Von Ludin dynasty in Sweden. He gives her the world materially, but her skin colour never finds acceptance from his parents and when Kemi sees her as a gold-digger during their first encounter she feels it differently in the form of betrayal from her “sister”.

Also, this novel reechoes the call made by Dike Chukwumerije’s classic poem, The Wall And The Bridge, reminding us of how we accuse the West of racial discrimination and look the other way regarding our own tribalism and subtle apartheid.

Rating: 4.5/5 Stars.