“Presbyterian Nursery and Primary school was made up of two simple blocks and a church hall beside the field,” begins this tender, coming-of-age novel that discusses in hindsight, the remains of childhood and adolescent memories of Nosike, the narrator and the lead character.

Readers are introduced to a perfect child who consoles his crying classmates, protects his siblings, plays football very well, and brings home excellent results at the end of every term.

As we delve into the book, we come to realise why the words “school” and “church” appear in the opening sentence of the book. They turn out to be the major agents in the socialisation of Nosike.

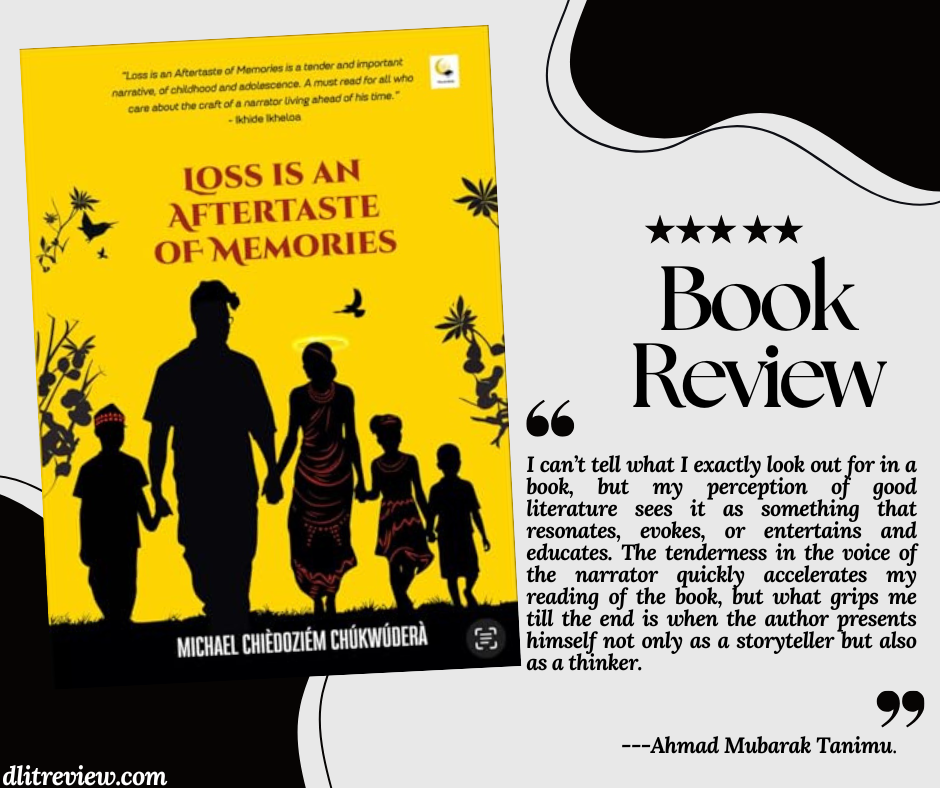

I can’t tell what I exactly look out for in a book, but my perception of good literature sees it as something that resonates, evokes, or entertains and educates. The tenderness in the voice of the narrator quickly accelerates my reading of the book, but what grips me till the end is when the author presents himself not only as a storyteller but also as a thinker.

On page 8 of the book he writes:

“I look back now, and I learn the lesson that one always comes to realize that the level where he once saw himself as highly placed in childhood, was only a stepping stone. For now, when I see children at that stage where I was then, I can’t help but think about the enormity of what lies ahead for them. ”

The passage above resonates deeply with me. Even after my secondary school, I was buzzing with great expectations for a smooth and great future. But the first humility I received from life was chasing a degree program without success until five years later.

The award-winning novelist, Chika Unigwe taught us in a writing workshop that a story is a disruption of routine. For Nosike, his story begins with a mysterious leg injury that afflicts him in his final days of primary school,

“Shortly into the school term, I was beginning to feel pain in my left foot. The itching that came with it made me stamp my foot on the ground often to ease myself of it, ” he narrates, “sadly, each stamping of my foot only increased the pain.”

This foot injury rattles everyone around him. His parents move him from hospitals to a prayer house in search of remedy. Details of the cause are kept obscure from readers and the narrator almost goes speculative in discussing it when he remembers kicking a plate of food meant for a sacrifice to Ogun prior to the injury, but he dismisses it by saying “I was sure the event was only a dream”.

Relating his father’s ordeal in those sleepless nights occasioned by the injury, Nosike says “I still remember vividly the tone in which he prayed and I am convinced that if the pain was a palpable thing, he would have picked it up from my foot and dropped it on his; but sometimes in life, all we can do while we watch those we love suffer is to be there and bear witness to their pain.”

Nosike’s foot was operated on in the end after a frustrating quest for medication from one hospital to another and over a litre of pus was drilled from it even as the doctor conceded to not knowing the cause.

Sibling rivalry between Nosike and his immediate younger sister, Adaora comes into the story with the father always on the side of the sister. Nosike’s preferred choice of secondary to enrol was altered by the economic setback faced by his father in the aftermath of the robbery of his father’s shop. So, he settled for a school that was known to be a breeding ground for both obedient and wayward kids.

He started well, but his inability to make it to the football ball team of his class punctured his happiness. He soon found himself influenced by some friends into insolence and was skipping catechism and not paying attention to learning in school.

“…doing what is forbidden could be very exciting,” says the narrator later becomes an adult. “One thing clear to me now from the standpoint of memory is that once you began to break a new rule it wasn’t much longer before you began to break another, and another.”

He almost got himself killed in a river after leaving home in the name of going for catechism. This face to face with death devastated Nosike but he kept the incident to himself until a neighbour told his parents. This period of insolence in his life coincided with a poor run of results from school despite the reprimands from his parents.

Love changed Nosike. First from his Edo language teacher whose tenderness towards him revived his enthusiasm for reading and improved his results to a level befitting of his academic potential. Reflecting on her influence on him in hindsight, the narrator said “I have come to realise how love and attention is more of a powerful tool to a teacher than criticism.”

Secondly, he fell in love with a beautiful girl, Nneoma whom he met in catechism. The need to look attractive in her eyes shaped Nosike into putting his best behaviours all the time. Fortunately for him, the girl was a sapiosexual and his display of knowledge of names of various religions in the world during congregation when the pastor asked the worshippers to mention them impressed her. It marked the beginning of their mutual affection.

Nosike and his younger brother’s time in the market with their parents was put to a halt over his constant involvement in fights with other adolescents. “If a monkey goes to Eke market and fights, goes to Orie and fights, goes to Afo and fights and repeats the same in Nkwo, it becomes harder to believe him when he says he is not the offender,” the author went philosophical in explaining Nosike’s attitude in the market before his father arrived at the decision to stop him from going in the interest of peace.

The book is made up of 31 chapters and after reading the first 28 chapters I started asking “I’ve seen memories in it, where is the loss?”

The loss arrived in chapter 29 and it was huge. Nosike and his siblings woke up one day with news of the sudden demise of their mother and again of a mysterious illness kept obscure from readers.

What a debut for Chukwudera. I’m stunned by his artistic maturity. I haven’t read a well-crafted simple and linear story in a while like this one. The only place where I find the book underwhelming is when Nosike almost drowns again in a lake in the village. The aftermath of the incident and Nosike’s inner thoughts seem a repetition of what happened to him earlier in the book and this slows the urgency that the author adopted in telling the story from the start.

Coming-of-age novels, especially for boys, are not what we often see in Nigerian literature. Though Chukwuebuka Ibeh’s Blessings is premised on a similar theme, the two books differ swiftly regarding the central character as that of Ibeh is about the epiphany of a gay boy.

In Loss is an Aftertaste of Memories, Nosike is hit by a car and spends months in a hospital bed. The accident and his recovery herald a new moment of love, friendship and care that touches him deeply.

This book sent me into revisiting some of the vital moments of my childhood and adolescence. Find time to read it and pick things to reflect on. You will agree with Chukwudera for saying “There are indeed so many things lost in the innocence of childhood for lack of understanding.”