Obioma revisits the Nigerian civil war in this skillfully written prose, The Road to the Country, which is full of heart-piercing metaphors. He juxtaposes mystical and physical realms in telling the story. The book is a carnival of stories of the Biafran dead.

For his writing style and nuance, The New York Times in 2015 declared Obiọma “the heir to Chinua Achebe”, but we can also see the influence of Wole Soyinka in taking African deities to the fore in this ambitious novel. Albeit, the imprints of Achebe on Obioma are still seen in this book right from the choice of title. Achebe’s Biafran story, though a memoir, is titled There Was A Country and we can see how the word “country” finds its way into the title of Obioma’s Biafran story.

In 1947, as we read in the novel, 20 years before the war, a seer, Baba Igbala, an Ifa priest in Akure, saw the war in an eight-hour-long vision shown to him by Ifa. In the vision, the seer sees a star; he watches the birth of the star, the eruption of the star, and lastly, the expulsion of the star. The star has a name, and the name is Kunle.

The Nigerian Civil War is probably part of our country’s history that interests me the most. For the North, the East, and the West still appear to learn nothing from it.

Back in June, in Abuja, the award-winning novelist and the convener of Flame Tree Writers Project, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, identifies Cyprian Ekwensi during the Flame Tree Writers workshop as one of the early contributors to the development of Northern literature.

Ekwensi was a writer of Igbo descent whose early works are completely Northern in settings and characters, thereby promoting the culture of the North even ahead of his own Igbo culture. African Night Entertainment and The Passport of Mallam Ilia are some of the living evidence of Ekwensi’s appreciation of the North and its culture.

But Ekwensi fought in the war as a soldier for the secessionist Biafra. So, Abubakar, in an interactive session, asked the participants why. I was there and my reply was “Things fall apart!”. He didn’t find my initial response satisfactory, so I gave another, and this time, I said, “the pogrom”, and yes, it was the response he was looking for.

While Chimamanda Ngọzi Adichie’s Half of A Yellow Sun attempts to point out some of the precursors to the 1966 Igbo pogrom in the North, Obiọma pays little or no attention to that in this book, instead, he presents it as the most motivating factor behind the Biafran resistance in what was a one-sided battle between those willing to die for their rights to self-determination and those ready to kill them, if that’s what it takes to deny them.

The Nigerian civil war is a melancholic memory and The Road to The Country provides readers with a detailed cost of harboring resentment. It is the mutual resentment between the North and the East that starts the war, and in this story, it is Tunde’s resentment for his older brother, Kunle, which leads the two Aromire brothers to get involved in a war that is not theirs to fight. A simple act of Forgiveness and moving on could have saved them from future torment.

Before the war, Tunde had an accident that tempers his spine and confines him to a wheelchair. He blames Kunle for it. The accident enjoys several mentions in the book but the author keeps the details somehow obscure from readers. This happens to be one of the aspects of the book that I find unsatisfying. It looks like a suspense plan going wrong. Obioma builds a serious conflict around the incident but keeps shying away from discussing the details, especially on why Tunde thinks Kunle is culpable in full till the end.

Tunde finds solace after the accident only in Nkechi, their neighbour and his brother’s girlfriend. Nkechi, too, joins Tunde in the resentment of Kunle and transfers her affection to the younger brother. When the war starts, Tunde joins the Agbani family (Nkechi’s parents) to relocate to the East. A decision he would later regret. However, there is something very hard to believe in the story of Tunde’s elopement with Nkechi. Tunde is a teenager in a wheelchair. I am curious. How did he escape the surveillance of his parents to embark on the dangerous journey to the East?

Despite his exoneration by almost everyone who heard about the accident, Kunle too blames himself for his brother’s disability, so, when information of his brother’s elopement reaches him in Lagos, where he studies law at the University of Lagos, he sees an opportunity to make his parents happy in a move to redeem himself of the earlier mistake he believes to have made by travelling to the war-torn Eastern Nigeria to bring Tunde back home.

When Kunle reaches the East, he is caught, conscripted into the Biafran army, and renamed Peter Nwaigbo by his conscriptor, which marks the beginning of his layers of ordeal on the battlefield. He finds himself fighting a war without rules of engagement. He makes friends who he fought with side by side, and the mass killing of Biafrans would make him fight the war like it is his. Obioma writes:

“He was derailed from his first mission, to rescue his brother, but the war has since given him other things he had not requested.”

The war gives Kunle Agnes, a brave woman he falls in love with whom he would make love amidst shellings and bombings and have a daughter. He betrays her trust when faced with the dilemma of saving her and the baby that she carries on the battlefield or allowing her to fight on as she desires. His friends encourage him to save her and the baby by confessing their affair to the foreign commander they fight under. Steiner, the commander, sends Agnes to work in a Biafran hospital since she is a nurse by profession. This angers Agnes into separating from him.

He runs into Nkechi’s brother, now a Biafran soldier in one of his visits to the hospital where he hopes to find Agnes. Nkechi’s brother leads him to where he meets his younger brother. The author describes the emotional reunion:

“More than a year ago, he set out on the journey to Biafra, thinking it would be a short road to his brother, but the road has been long, muddy, and rough. And now, after many detours and roadblocks, through a thousand collisions of life, he is gazing down at his brother.”

Devastation is so common and everywhere in this book that, as I read, it is in rare moments of relief in the story that I find myself fighting tears. Obioma’s vivid description and eloquent telling of the Biafran misery is a mirror for readers to see not just what happened in the past but also see the reminiscent of what Palestine is going through; the devastating consequence of war against a powerful and malevolent opponent that enjoys the support of the world superpowers.

“Maybe…maybe life is jus a necessary evil.” Says a Biafran soldier whose resilience is stretched to the limit of questioning the essence of life.

Beyond the indiscriminate bombardments, the more devastating part of the war is the blockade. Obioma captures the prevalent case of hunger in Biafra, occasioned by the economic blockade through one soldier, who says in a joke:

“Biafra is the only country in the world with no fat people.”

Salt is probably the cheapest food item in the world, but the blockade turns it into gold in Biafra. Another devastating moment for Kunle is when he sees a boy sitting and crying next to the dead body of his father, killed in error as a saboteur after picking a salt during the Afia attack. A white mercenary fighting for Biafra later adopts the boy.

When Kunle runs out of money because the Biafran 12 Division he later fights under is not paid; instead, they donate their salaries to a group of farmers to farm and feed the country, he opts to use his pistol to get whatever he wants.

When not only weapons become difficult to afford for Biafra, but uniforms for military personnel as well, following the request of his younger brother to stay alive at all cost and return to take him home, Kunle convinces himself that the war is won and lost and so he escapes to Ikot Ekpene, the nearest town under the control of the federalists to surrender. As Obioma writes, this is how Kunle finds the disparity between the Biafran and the federal troops:

“He can hardly imagine the abundance of the federal troops—everywhere, even in the smallest quarter of the camp, are vehicles. Tanks, command vehicles, petrol tankers, personnel carriers, wagons—and near the perimeter wall, the remains of a Biafran Red Devil tank gathering dust. The officers are well-groomed, perfumed, in polished shoes.”

After the Biafran surrender in January 1970, Kunle returned to the East for Agnes and Tunde. He discovers that Agnes went back to the battlefield the day airstrikes killed her mother in the market, and she did not survive the war, but she left a daughter behind for him.

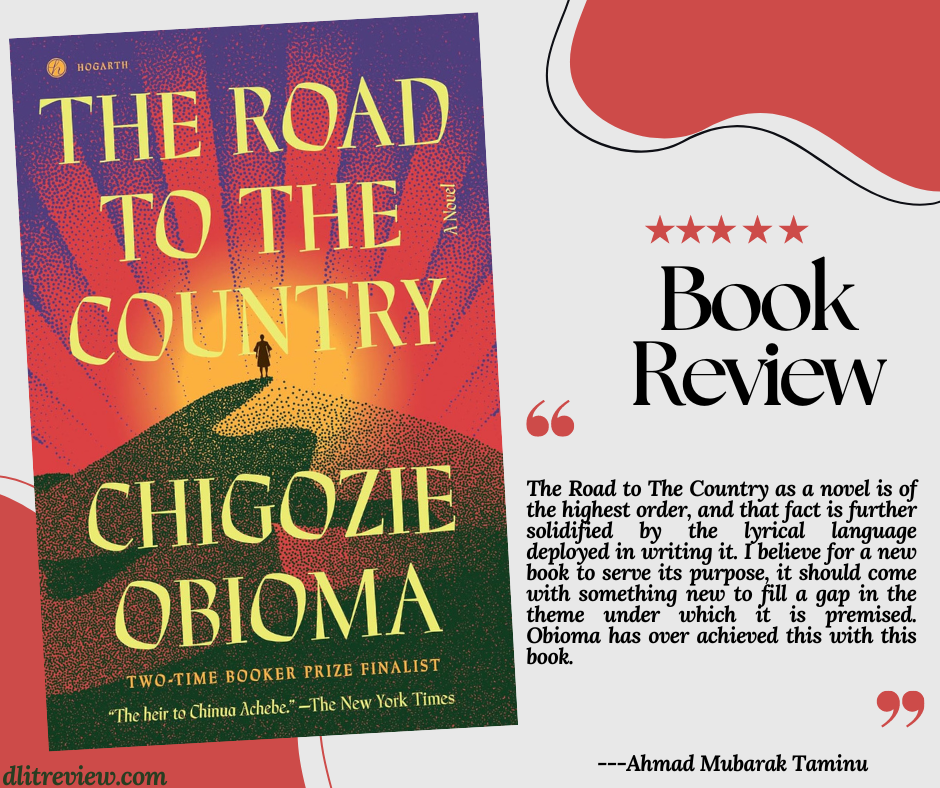

The Road to The Country as a novel is of the highest order, and that fact is further solidified by the lyrical language deployed in writing it. I believe for a new book to serve its purpose, it should come with something new to fill a gap in the theme under which it is premised. Obioma has over achieved this with this book.

However, I find the execution of the central plot of this story not meticulous enough. The character of Kunle is not easily believable. One ambitious goal that Obioma sets to attain in this book is to tell the Biafran story from the point of view of those killed and forgotten in the war. He announces this in the quote below:

“It occurs to him that the only true thing about mankind can be found in the stories it tells, and some of the truest of these stories cannot be told by the living. Only the dead can tell them.”

So, to give the dead a voice to tell their stories, Obioma’s character, Kunle, suffers a shrapnel shot on the head that sends him into a coma. His soul travels to the afterlife for days and meets different dead people who were not buried, wondering about and telling how they die. Then returns to this life and continues fighting as a soldier after the healing of the shrapnel wound. In Game of Thrones, when Jon Snow travels to the afterlife, he remembers nothing upon his return and I find his story more believable. Nevertheless, The Road to The Country is a precious addition to African literature.

As I mentioned earlier, the book is an eight-hour vision set in 1947, hours before the birth of Kunle. After his birth, Baba Igbala goes to his parents to reveal what he has seen of the child’s future, but he gets this as a response:

“We don’t want whatever you have seen,” the man says. “We are Christians…We don’t believe anyone can see the future, and not the future of our beloved son, who was born not more than two hours ago.”

Igbala’s vision comes to pass and the war happens. May it never happen again.