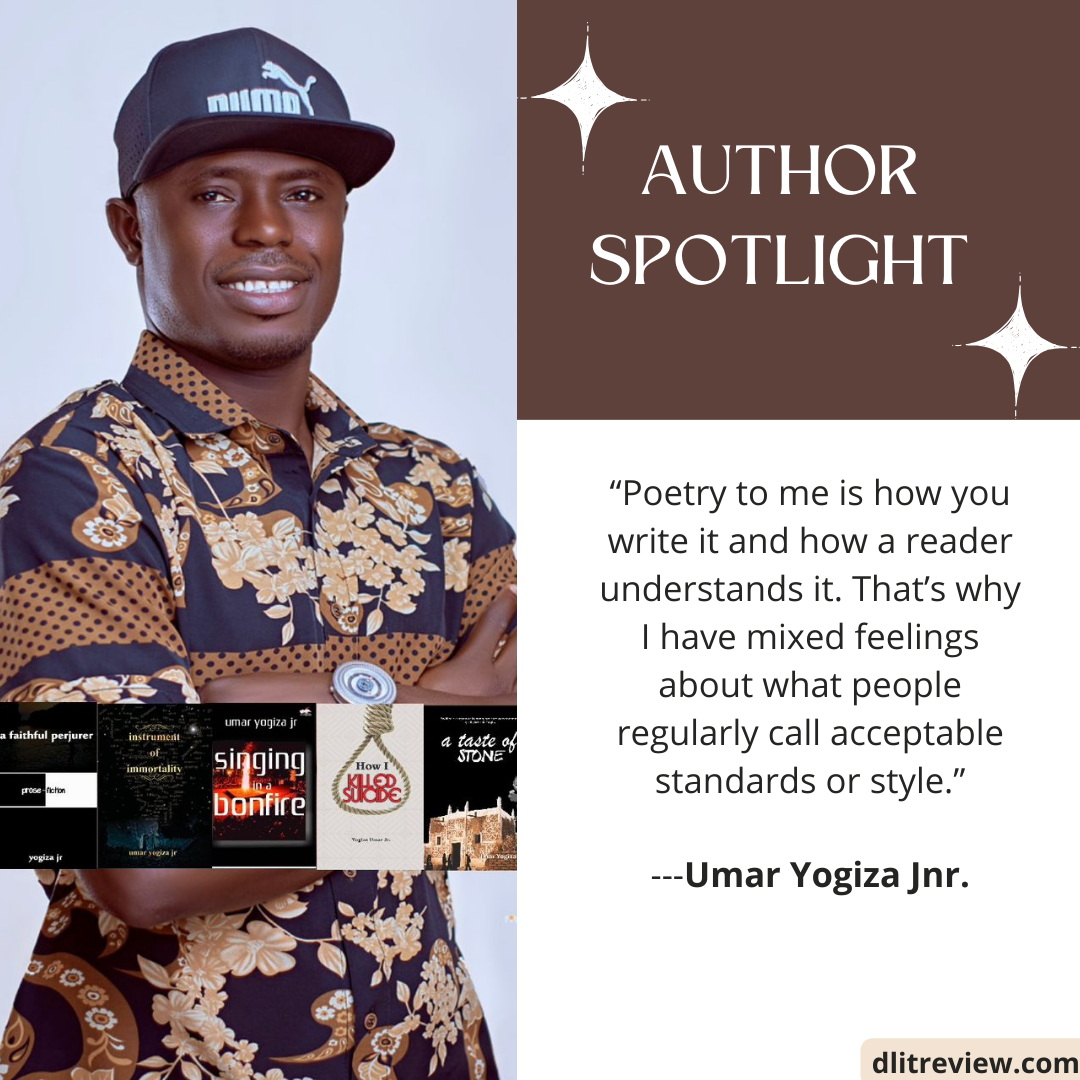

“We gave our arts’ approval to foreigners…” In Conversation With Award-Winning Author, Umar Yogiza Jnr.

Umar Yogiza Jnr. is an outstanding Nigerian author who, among many feats, won the 2017 Atlanta Georgia Black Street Poetry Prize and has been a Pushcart Nominee.

In this interview, he shares his journey, the ups and downs African writers face, and what keeps him going.

Q1: Can you share a bit about your journey as Umar Yogiza Jnr., the poet and writer, from your first appearance in the 2008 Anthology to winning the Atlanta Black Street Poetry Prize in 2017?

My journey into poetry began, I think, between the year 2001 and 2002, I remember our English Language and Literature teacher in GSS Giza, Mr Agiligi, always made us read, over and over, and crammed poem after poem, and later, I fell in love with ‘No coffin, no grave’, by Jared Angira, and later, I gave the poem so much of my attention that I became restless in my expanding thoughts and reasons.

In reaction to Jared Angira’s poem, I started writing poems. I think I wrote more than twenty poems after that particular poem of Angira. And there is this one particular poem I carefully wrote of twelve lines, I cannot fail to remember, after Jared Angira’s ‘No coffin, no grave’. Let me bring some five lines that I can’t forget in the poem:

Life is not the beginning and/The burial and the grave is not the end/ The rain cannot anchor/What the rain didn’t know, like us/ Postmortem can be anything.

One day, with Nuhu Agbo: a close friend and classmate’s bold push and creaking confidence, I gave our teacher Mr. Agiligi the poem, and immediately, he fell in love with the poem; so much that he invited me next day to his house, where we ate pounded yam me; he gave me three brand new full poetry collections: JP Clark’s, Kofi Awoonor and Niyi Osundare’s. I watched him with utmost reverence and awe as he rewrote my poem with his fine, calligraphic handwriting.

When water spoiled the large left edge of the paper containing the poem, he had me add three more poems afterwards. He took the poem to Makurdi as he said and after a year or so, the exact month I’ve written my WAEC, the poem, Mr. Agiligi said, had won the Association of Nigerian Authors Prize in Lagos. How can you replace such intimidating joy at such an age?

The Atlanta Black Street Poetry Prize in 2017 to me is a stamp. It gives me a small voice and veneration. It quickens the body of my passion and writing.

In Nigeria, acceptance, assistance, recognition, and sincere encouragement are virtually nonexistent until someone outside Nigeria notices, appreciates, or acknowledges you as a writer. Only then do people at home recognize, appreciate, or even associate with you. Until then, you are nothing.

As young poets, we struggled and were ridiculed to be recognized, to be called writers and poets. We were afraid to even answer the name writer and poet. That’s how bad! No journalist would interview you until one foreigner gives you an award or writes about your craft.

Q2: Your journey from leaving art to science and then finding solace in poetry is intriguing. Can you tell us about the moment or period when you realized that poetry was your true calling?

I did an art focus secondary school: GSS Giza, my first WAEC and NECO were all arts results. After secondary school, where I work, the Nigerian Institute of Building fascinated me, seeing the Builders and Engineers that fascinated my aunt. I registered for another NECO and WAEC for sciences in Lagos, and that’s how I switched from Art to Sciences, but I had already won a small poetry prize a while back.

Engineering is a profession, but writing to me is a portal from one person to another, a delicate door made of words and language. I believe we open this door every day in our lives. And I feel very privileged to be a poet, a writer, being a voice, to have books; vessels that sail my kind’s stories and history across so many fabricated obstacles. I am free to interrogate my pain, my choice, my history, my opportunities, and my future. I am free in poetry to interrogate what my kind couldn’t survive.

There was a day I played my late mother a video of one of my readings, this was in Abuja and it changed the way I see poetry. My mother, like almost every other parent in the little village of Giza where I grew up, doesn’t speak English, but they all knew the value of education.

My mother watched the one hour plus of my poetry readings, after the reading, the questions and the ovation. When I turned to my mother, I saw that she was crying. Kaka? I said! But you don’t understand English what the people are asking. Why are you crying? She held my head, looking at me and said, with a tearful smile, even white people are clapping for my son. Clapping for my son, she repeats. The type of people she’s always mute around at work, the type of people she’s often invisible around at work, the type of people that are now clapping for her boy.

That was the first day I felt fulfilled as a poet, seeing the excruciating joy it had given my mother. Here is a woman who’s a cleaner and messenger to the people of the English Language. I think for the first time in my life I did something important for this woman who’d sacrificed her comfort for me, since that day, every clap, every joy is for my mother, for her struggles.

Averaged-class people like me, whose parents weren’t noble or educated, didn’t get a chance to be heard or have a voice. Many of us were erased because of being heard or wanting to be heard. The history of my kind’s success and survival has been wrought long ago with hardcore violence, fear, and disorder that most of us failed even before we started to dream. People with real stories to tell that just didn’t get to tell.

Poets with the next award-winning book are shining and mending shoes, opening doors as security guards in Lagos nightclubs, holding rusted guns at checkpoints, and working as house boys, that’s where a lot of my kind are.

Hard work is the only common, cheapest and purest form of generosity and contribution my kind has to give the world. I feel free in poetry, it’s the only genre that allows freedom in articulation. Every manipulation of the language adds meaning the same way Maggi adds meaning to soup. When you know that poetry is your calling is the moment turning away from the truth becomes the ultimate act of betrayal.

Q3: Your personal story, “How I Killed Suicide,” is powerful. Could you share more about how poetry became a transformative force in your life as Umar Yogiza Jnr. during that difficult period?

‘How I Killed Suicide’ is therapeutic, it’s a book of wounds, chapters of trials, paragraphs of scars, lines of healing and words of survival. The book is my journey into and out of depression. It’s a personal journey of silent pains and healing. Mental illness, no matter how small, its healing process is never a small journey. It’s dangerous and real, no matter how little its symptoms are.

Reading and expressive writing, especially poetry, had been employed as supplementary treatments for those experiencing mental or emotional distress in the United States and Europe, as early as the 1800s, by the likes of Dr. Benjamin Rush, pharmacist Eli Griefer, and later Dr. Jack L. Leedy and Dr. Sam Spector etc., who formed the Association for Poetry Therapy (APT) in 1969.

The story is about what happened to me, from the very beginning, how I felt, and what was going through my mind then and afterwards.

I remember when I shared the story online, my good friend and a literary promoter, Mr Eriata Oribhabor, who had seen the response the story generated online, promised to publish it, and he kept to his promise. He edited the work, through his publishing outfit: Something for Everybody, published ‘How I Killed Suicide’ and transported the book to me in Abuja. That’s how kind and generous he is to any meaningful literary work.

And thank God, How I Killed Suicide has helped so many people out of depression. Even people who do not know they are depressed. Had I read a book like, How I Killed Suicide, I would have made a truce with my warring minds, I could have taken this gigantic monster within well-prepared. It wouldn’t have reached the depression stage, talkless of suicide. How I Killed Suicide is a cheap, common, easy guide to establishing a realistic sense of self-worth, self-esteem, and internal empowerment. It’s an inspirational journey and a border map, leading towards nothing but a cure, driven by soul containment and peace of mind.

Q4: In your profile, you’ve mentioned breaking away from set rules in poetry. Are there specific poets or writers who have influenced your unique approach? Whose work resonates with you, and in what ways?

The meaning of a poem to me is not in the page of paper, or even the poem itself, but it’s in whatever our minds do with the poem at that particular time. To me, in a good poem, there should be discovery, mild entertainment and dense surprises. Poetry is not an all-out war, nor is it an all-out peace. Neither is it all-out foolishness nor all-out wisdom. Poetry, historically, has always been the holder or mender when things start falling or fall apart completely.

I have come to realize that the English Language often subverts the meaning of whatever I want to communicate as a poet: my poverty of the language at times demeans the potency of the mystery and sensation of my intentions. Whenever I write a poem, it’s like I’ve created a city, that readers can do whatever they want in it to bubble. I don’t want the use of English to spoil the potency of my poem. I don’t want my city to be what my readers don’t want it to be.

Poetry to me is how you write it and how a reader understands it. That’s why I have mixed feelings about what people regularly call acceptable standards or style.

Poetry is only a sanctified and liberated place affordable and available, where we meet the raw form of our true selves, where we feel the guilt of so many generations and things, and where we show sincere concerns towards individual or societal ills.

Poetry is the only place where we speak perhaps more humanly and openly unafraid. And personally, poetry is the only place we have the moral liberty to speak as the mouthpiece of what cannot speak.

Q5: Congratulations on translating ‘Instrument of Immortality’ into French and Filipino. How has the reception been, and what motivated you to make your work accessible to a wider audience?

It’s translated into four languages, actually. Translation of the Instrument of Immortality into four languages wasn’t my making, I think. It surprises me when people love the book. It was first translated into Filipino by my Filipino friend Dr. Ruiz, during or immediately after her PhD, then a PhD research student and publisher in France, also a friend inquired about translation and I said yes.

I love the German language, and love the German language translated version of the book. I had many German friends then. A lecturer and former diplomat whom we met through Free Poetic Universe, he translated the book into German language and donated all the one thousand translated published copies to the refugee schools in Germany. Later, a group of research fellows translated the book into the Swahili language.

But a professor in South Africa last year complained that the Swahili version of Instrument of Immortality is a poor translation after he read the original e-copy of the book I sent to him. For me ooh! Presently I don’t care, the accessibility of the book is more important to me. Holding my books in different languages gives me joy, holding that void-filled space with humour and real grief in another language feels beautiful and strange.

Even in an alien dialect, in each poem I can still feel the burning desire and hunger of so many of my kind, to pass a message, to speak the raw truth, to be free and mindless of all the danger of revealing the truth.

I sometimes think in every language that desires to unearth the centuries-buried dream, opportunities, tastes, desires, and recovery surpasses all the terror for a writer.

Q6: As the founder of Free Poetic Universe, can you tell us about the goals and vision behind creating this online poetry group?

The Free Poetic Universe quickened in the year 2014 when a Facebook literary group, Literary Planet, owned by the Philippines, banned fifteen of us poets.

Five Indian professors, one Philippine, and four Nigerians: Eriata, Dr. Uzo Nwamara, me, Thomas Peretu, and Martin Ijir.

So I decided to open a group that’s present everywhere, not only on Facebook. From Facebook, we created a site, spread it into Twitter and so on. Did three anthologies. I tried in everything I do to leave behind the large unuseful things and focus on the tiny, tiny useful things that are practically before me.

Waiting for a good outcome out of hopelessness leads only to heavy failure and a life blame game. I think that no matter how difficult life is, I have a choice of how I channel my energy and opportunities.

It surprises me when people treat people as less important because of their level of education. We regard people as unintelligent simply because of their illiteracy. We live in a culture, I think, where failure seems doomed, no matter how one tries, no matter how high the huddles before his background. Likewise, we often forget fate’s odd way of creation, we often forget all the hard work and dedication someone puts in when he fails. Our minds were so fixed on the glows of success that we forgot to appreciate those who failed in what is not practically their fault.

Q7: How do you see platforms like Free Poetic Universe contributing to the global poetry community?

The Free Poetic Universe has well over ten thousand members, beyond three thousand university professors and PhD holders. We collaborate and work together, and we have accomplished three international anthologies of poems. Formed publishing and editing boards across the globe.

Even coming together with all our barriers and differences is an achievement. One can travel to any country, any part of the world with the assurance that one has sincere friends whom one knows on a personal level and with whom one had worked together for the love of poetry. To me, that’s an incomparable contribution to global poetry.

Q8: Umar Yogiza Jnr., you are a trustee of The Center for Empowerment of Indigent and Incarcerated Citizens, could you share more about the NGOs initiatives and your role in supporting the well-being of Nigerian prisoners?

The Center for Empowerment of Indigent and Incarcerated Citizens (CEIIC), is a joint venture. For me, it started with my prison visitations. Societal problems, I think, whether good or bad, like hunger, embrace us— at times whether we like it or not.

As much as society has the capacity for good, it also has the capacity for evil. Even though we aim for good for ourselves, there are times we meet bad luck, intentional or unintentional.

The day I met a good poet in Kuje prison; only my appearance brought him intense joy, and my perception of prison, prisoners, poetry, and the world changed. Great people don’t have time to be original or measure their greatness.

Since that day, I keep telling myself that to be great, I won’t pressure myself to be great. One doesn’t need to be rich or super famous to impart or help someone. After my second Prison visit, I decided to visit Kuje prison twice a year, donating books and used clothes. Prisoners appreciate the little we took as nothing. They have nowhere to go. Only a few of them keep their hope alive.

Many of them have given up on life. And so the prisoners appreciate people visiting them. Seeing people gives them hope, and making them laugh enlivens their souls. These things are very cheap.

What we are doing with the prisoners is not of interest to people; writers, poets and even the warden themselves. I remember when we were sent consecutively three times to the Suleja prison. They aren’t concerned with the lives of the prisoners they locked up.

How can you correct a person you locked up for doing bad to society? You can’t make someone human with only punishment, or suffer hardship without compassion.

The wardens are used to the big, big NGO and rich people’s visitation, but we are small: writers and wannabes. We may not have much but the ten, or twenty shirts, trousers, cardigans, and books came from within us; our pockets.

It’s hard convincing people to help prisoners locked away in prison. People thought it was not their problem. Our aims are only to give the prisoners delight, hope, and strict responsibility. We never pay fate to keep us safe, to make us sane, give us freedom, comfort and clean health. It takes nothing for fate to deform one’s life.

Going to prison, seeing the prisoners and giving them hope has a lot of pleasure and pain too. Not all of them are open to you. Some just look at you, and you don’t know what’s going on in their minds. It’s hard trying to give light to someone who’s always in darkness.

It’s very painful sometimes seeing young people your age or less with no idea, how to be positive, how to shape meaning out of his situation. Life gives us differences that others have no time to think about.

Q9: Umar Yogiza Jnr., you have a background in Building Technology. How do you balance your career in construction with your passion for literature and poetry?

Building and Engineering is a profession, but poetry is a sanctified devotion. There is no money in poetry, but there is personal fulfilment. You’ll have to give up any entitlement to be a poet. The trauma of success is an integral reality for aspiring young poets, but not if it’s personal fulfilment.

They make joy and success rare and foreign in the foundation of poetry, simply by existing as a poet you face to face with danger. Sadly, we live in a culture where one needs to be recognized as a poet outside or by outsiders before we recognize and appreciate them as a poet at home and in our public spaces.

Being a poet and making a living off poetry, especially young poets, it’s very, very hard for young Nigerian poets, extremely hard.

There’s no organized body to support our hard work. And I think that’s why poets these days have no time to give delight to the readers, they give responsibility. I would rather not make things very hard for my reader, a time when poetry is like an examination has passed.

Q10: What other works have you enjoyed working on? And do you have any upcoming work? What can readers expect, and what themes do they explore?

My new collection: A Taste of STONE, published December 2023, is, in fact, an old work of mine. The work I am on presently is a work I revere so much that I put everything into it.

It’s a historical project. I delved into my history, the history of my forefathers. The aftermath of Danfodio’s Jihad in Northern Nigeria. A history surgically preserved by the atrocities of the perpetrators.

I am a curious, factual person. I don’t know if sincere curiosity is magic at times to me. The history I’m exploring at times makes me angry, and at times makes me proud, sad and silent. Events past, present, and time move I think more in a spherical dimension than it does in a straight line. Every time I write, I am confronted with these repetitive traumas as if I was there so, so many years ago.

Q11: Reflecting on the current landscape of African literature, where do you see its strengths and areas for improvement? How do you perceive your style as Umar Yogiza Jnr., contributing to or challenging the existing narratives in African literature?

If the Greek root for ‘poet’ is ‘creator,’ then we should learn to create what resembles us I feel, mindless of the obstacles we have upon our necks.

The current landscape of African literature or today’s creativity is no longer fertile, don’t get me wrong, the craft is fertile, but the landscape at home is not. We believe more in what others think or say about our crafts than what we think of ourselves.

We gave our art’s approval to the foreigners. You have to leave Africa to succeed or be appreciated as a writer. We have allegiance to a lack of sincere appreciation, negligence, and abandonment. We underappreciate, neglect, and abandon until when someone appreciates that thing before we claim relationship and ownership.

There are these abstract feelings we crave in everything foreign and aversion to our Africanistic imaginations. No matter what, I think we should learn to leave a home in our thoughts and feelings even if we are no longer at home.

I believe each time we think or reason without Africa, something African departs out of our creativity. For, thoughts, feelings, and reasons to me are home on their own. Wherever we are doesn’t matter, but our feelings. We could be on the moon, and it would still feel like home.

My style? I don’t think I have a style. I only write poetry in a way that everyone, mindless of their career would understand, not only poets. Likewise, I don’t want to write fancy poems; well-dressed poems that have no place to go. The past has made poetry deliberately difficult to read and decipher.

For me, Umar Yogiza Jnr., there are times to write for poets and literati, but not always. Mundane poetry has distanced itself from social structures, what we are doing now is mending the relationship. Bringing people back to poetry.

There is liberty in poetry, we should let people devour poetry with joy and happiness in punishment. Poetry lends itself to any kind of distortion, so why not take advantage of this angle and make it enjoyable?

Art is like Nigeria, it’s worse until you enhance it, we should learn to always forget the past; how it was in the late 80s, 60s, 20s and so forth. There was a time when people thought the explosion of poetry was causing great havoc and destruction in the affairs of the unfair society.

But as time goes on, the standard falls; living standard falls, educational standard falls, thoughts and reasons standard falls. Things became bad. People’s anger lost direction. The poor becoming poorer are angry.

The elite is corrupt and has corrupted everything, and the more corrupt things get, the easier it is to blame the past or Lord Lugard, the North or the past administrators for it but our present selves. The more we don’t take responsibility for our actions. This is a big problem, even with Art.

Q12: As an experienced poet and writer, what instincts guide you in knowing when your writing is ready for acceptance after submission?

When what I am writing resembles the magazine I am writing for, that’s when I know it’s ready. We should know that each magazine has its taste. To be accepted in a magazine, a writer has to forget what he or she wants. He or she must check the given themes, the rules, and the regulations. What the magazine wants becomes Literature and not what the writer thinks.

To me, a mature writer doesn’t care much about magazines, but how to better his craft.

Even though these magazines bring exposure, they control a writer’s thoughts, and they put a limit on what a writer thinks. They don’t encourage spaces where a writer, especially African ones, talk about their real traumas. Most foreign magazines accept work that fits with their taste and cohesive style.

Poetry should have been the medicine that heals so many years of silence, so many years of dispossession, so many years of wounds and scars and healing. It’s not supposed to be dictatorial, as most of these magazines make it to be.

The vulnerability these magazines bear in a young writer is larger than the courage they instilled. These trends make young writers no longer own their voices about everything that happened to them or their history that’s dying to be heard. To excel with a mask is not a talent liberation to me.

Q13: What words of advice do you have for emerging platforms trying to improve the literary scene, especially in Africa?

Platforms, either old or emerging ones, should be a breeding ground and let talent make it fertile, it should be where we can show the true colours of our talents.

Where we are free to say what is hurting in us is when we truly are hurting.

Platforms should be where real interaction exists, it should be where a writer can honestly and unapologetically write/talk without sanitization and sugar-coating for the sake of acceptance.

We can’t be ourselves without being open and vulnerable. Platforms should not be the ones permitting the writers to write, rather a writer should be the one permitting or dictating with his words.

Q14: Any last words for growing poets/writers?

Lack of opportunity should not make you turn to what you are not or make you yearn for the shortcut.

Read more than you write, read everything, even the writers you don’t like, or don’t enjoy reading. You’ll love one thing or two there.

If you don’t like a writer, you’ll love the binding of his book, the fonts, or his page arrangements.

There are just so many things you’ll learn by opening a book apart from reading.

Also, let the lack of opportunity make your talents yearn for redeeming the system or the future, rather than changing who you are as a writer.

There should be cultural preservation in our works, even though we are amid rapid globalization. We should incorporate and prioritize our indigenous identity. We should put prestige and loyalty to our lineage, our dialects, our traditions, and our culture, no matter how wide globalization has eaten us.

You can connect with Umar Yogiza Jnr., on Facebook, Instagram and X (Twitter).